Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales: final report - Chapter 4: protecting devolution

Final report of the commission detailing options to strengthen Welsh democracy and deliver improvements for the people of Wales.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Introduction

This chapter reviews the workings of inter-governmental relations. We make recommendations for changes needed urgently to protect devolution, whatever constitutional model the people of Wales choose for the long term.

The relationship between the devolved institutions and Westminster is a crucial pillar of Welsh governance. In our interim report we noted that in recent years relations have become fragile and unstable.

Devolution in 1999 was a major step forward for democracy in Wales, and in 2011 the popular vote endorsed the devolved institutions as a fully formed system of government with primary law-making powers. The fallout from Brexit has exposed the fragility of this governance structure. The UK government and Parliament have overridden the Sewel convention on 11 occasions since the 2016 referendum to leave the EU, with virtually no scrutiny or challenge at Westminster. In these cases the Welsh and UK governments agreed that consent was required; in one of these consent was given except for a late amendment where the timetable did not allow for Senedd consideration. There were a further 5 cases where the UK government took the view that consent was not required but the Welsh Government believed that it was.

We make no recommendation as to which long-term constitutional option is best for Wales; that is a decision for citizens and their representatives. It is clear to us that the current devolution settlement cannot be taken for granted, and is at risk of gradual attrition if steps are not taken to protect it. Citizens should be able to choose ‘no change’, but without urgent action there will be no viable settlement to protect.

Citizens’ views

The call for governments to work together to deliver efficiently in the public interest has been a strong theme in our evidence. Many of those we heard from expressed frustration at what they see as ‘political point-scoring’, ‘being different for the sake of it’, and governments working against each other instead of co-operating to improve life for citizens (these points were made in the online survey responses, in citizens panels and in some of the community engagement fund reports).

Co-operation

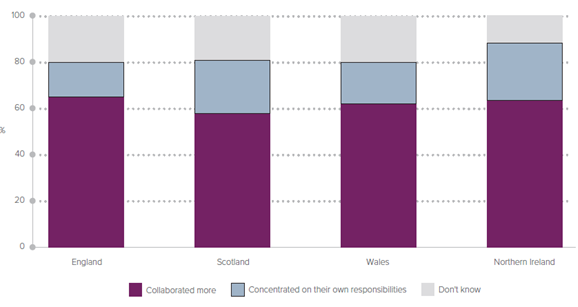

The State of the Union research indicates that in all 4 UK territories, between 58% (Scotland) and 65% (England) of respondents agreed that the governance of the UK would be improved if the UK and devolved governments collaborated more (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh).

Inter-governmental collaboration

Question: Which comes closest to your views?

- UK governance would be improved if the UK and devolved administrations collaborated more on issues of common interest

- UK governance would be improved if the UK and devolved administrations concentrated on their own responsibilities

- Don't know

Graph taken from State of the Union 2023

Citizens do not use the term ‘inter-governmental relations’ when they talk about how governments interact, but they make it clear that they want governments to collaborate. 92% of those surveyed believe it is important for both governments to work well together (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023). This holds true even if they dislike one of those governments: they exist, they are making decisions and they should work collaboratively (this view was presented in online survey responses, particularly the online engagement platform survey where there were specific questions on inter-government co-operation).

When inter-governmental relations fail, both governments fall in many citizens’ estimation. As we noted in chapter 2, people often do not differentiate between party politics, constitutional structures and public services. Citizens generally have very little time for governments blaming each other instead of focusing on improving services (this view was presented, occasionally forcefully, by respondents to both online surveys and through the community engagement fund reports).

Governments’ inability to work constructively together feeds disaffection with politics. Citizens see finger-pointing and blaming as a case of elected representatives promoting their own interests. In our online engagement platform survey, many people told us that they did not believe the UK government and the Welsh Government could ever work together constructively while opposing political parties were in power because this was not in the ruling parties’ interests (the online engagement platform survey included a specific question on whether the UK and Welsh governments could work better together in the future, a plurality felt that this was only a possibility when the same political party was in power in both Cardiff and London).

Citizens rarely used the term ‘mechanisms for inter-governmental relations’, but there was strong support across the 4 territories of the UK for a written constitution or independent mechanisms to resolve disputes between governments (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh – this point is explored more in chapter 6).

This support seems to reflect a sense of fairness, distinct from respondents’ constitutional preferences. Many respondents thought that such mechanisms would protect the things they value. For example, those who want to preserve the UK Parliament’s supremacy supported steps to prevent the Welsh Government exceeding its powers. Those who support at least protecting the current devolution settlement wanted mechanisms to protect the devolved institutions from being undermined by the UK government (the first 2 questions of the online engagement platform survey concerned a written constitution, requesting respondents shared why they would be for or against having one for Wales).

Respect

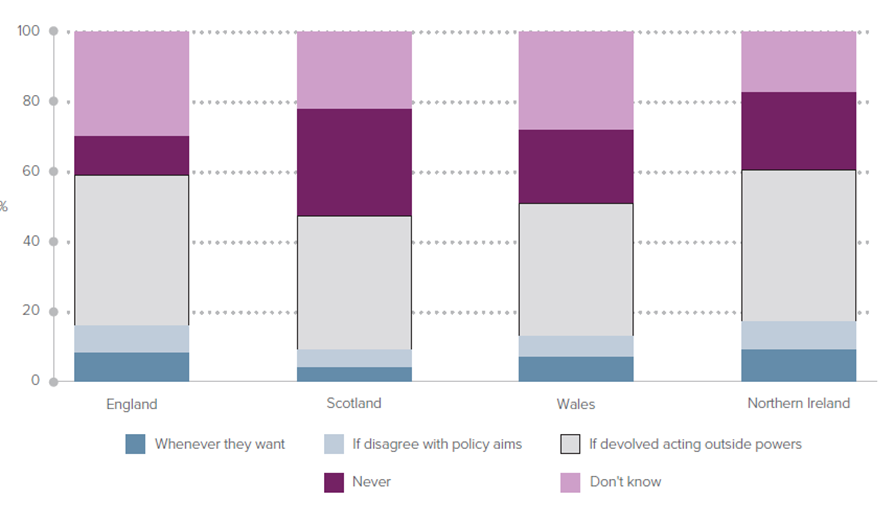

Our research reveals that citizens in Wales expect parity of treatment and equality of respect with the other nations of the UK. The State of the Union research shows that across the UK, citizens are in favour of respecting the devolved institutions and do not support UK government intervention or legislation on devolved matters without consent.

Amongst these respondents there was little support for a UK government attempting to block devolved governments from acting within their powers. A plurality of respondents favoured intervention only when the devolved institutions were acting outside their powers (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh). To note - ‘plurality’ has a specific meaning in relation to statistical analysis – the largest proportion, but not a majority.

Asked whether the UK Parliament should be able to legislate on devolved matters, only 17% in England said it should be able to ‘whenever it wants’ – proportions were lower in Scotland (12%) and Wales (14%) and similar in Northern Ireland, though there was a much higher level of ‘don’t knows’ (33%) in England, reflecting lack of familiarity with the issue (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh).

By contrast, 45% in Scotland, 37% in Wales and 37% in Northern Ireland favoured strengthening the Sewel convention so that it prohibited such legislation without permission or in any circumstances. The comparable figure was only 26% in England. When combined with the 28% who favoured the current Sewel principle of the UK Parliament legislating ‘not normally without consent’, this means that a majority of English respondents are in favour of at least Sewel approaches to legislation. There was a similar pattern in respect of the UK government’s powers to spend on devolved matters, with less than a fifth of respondents in England, Scotland and Wales saying there should be no constraint.

UK government action in devolved areas

Question: The current devolution settlements allow the UK government to block various activities of the devolved legislatures under certain circumstances. In which circumstances, if any, should the UK government attempt to block the activities of devolved administrations?

- If they believe that the devolved body is acting outside its allotted powers

- If they believe that the devolved body is acting within its allotted powers but they don't agree with the policy aims

- Whenever they want, the UK Parliament is supreme

- Never, the devolved bodies have their own democratic mandates

- Don't know

Graph taken from State of the Union 2023 (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh)

When should the UK Parliament legislate in devolved areas? (%)

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whenever it wants | 17 | 12 | 14 | 17 |

| Not normally without consent | 24 | 19 | 20 | 28 |

| Only with permission | 21 | 24 | 24 | 28 |

| Never | 5 | 22 | 13 | 9 |

| Don't know | 33 | 23 | 29 | 18 |

Question: The current devolution settlements allow the UK parliament to "legislate" on devolved matters for Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. Which of the following statements comes closest to your view?

- The UK Parliament should legislate on devolved matters whenever it wants

- The UK Parliament should not normally legislate on devolved matters without the consent of the devolved legislatures

- The UK Parliament should only legislate on devolved matters if it has the permission of the devolved legislatures

- The UK Parliament should never legislate on devolved matters

- Don't know

(Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh)

When should the UK government spend in devolved areas?

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whenever it wants | 14 | 15 | 17 | 22 |

| Not normally without consent | 21 | 18 | 19 | 23 |

| Only with permission | 21 | 28 | 27 | 29 |

| Never | 11 | 12 | 6 | 4 |

| Don't know | 33 | 27 | 32 | 22 |

Question: The current devolution settlements allow the UK parliament to "spend" on devolved matters for Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. Which of the following statements comes closest to your view?

- The UK parliament should spend on devolved matters whenever it wants

- The UK parliament should not normally spend on devolved matters without the consent of the devolved legislatures

- The UK parliament should only spend on devolved matters if it has the permission of the devolved legislatures

- The UK parliament should never spend on devolved matters

- Don't know

Table from the 2023 State of the Union report (Henderson, A., Wyn Jones, R., 2023, Public attitudes towards the constitutional future of the UK: Analysis from the 2023 State of the Union Survey, Wales Governance Centre and University of Edinburgh)

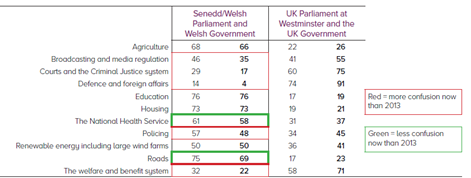

Knowledge and understanding

Most citizens have some understanding of how policy responsibilities are split between the UK government and the Welsh Government, but few have full knowledge. Despite the higher profile that the pandemic gave to devolution, public understanding has not greatly improved in the last 10 years (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023).

Who is responsible

Base: All 2023 (1,596), Commission on Devolution in Wales survey 2013 (2,009) Care should be taken when comparing the results of these surveys due to different methodologies (2023 = online, 2013 = Telephone) Comparisons made where possible.

Question: Here is a list of areas. For each one, please select who you think has main control of the area in Wales: the Senedd / Welsh Parliament and Welsh Government or the UK Parliament at Westminster and the UK government? (%)

- Agriculture

- Broadcasting and media regulation

- Courts and the criminal justice system

- Defence and foreign affairs

- Education

- Housing

- The National Health Service

- Policing

- Renewable energy including large wind farms

- Roads

- The welfare and benefit system

Figures in bold from Commission on Devolution Survey 2013

Chart from the 2023 Beaufort Research report (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023)

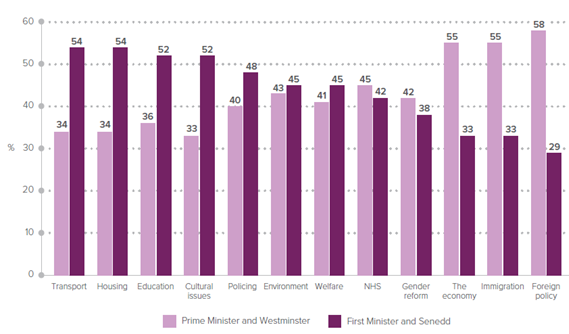

Who should be responsible

Question: In the following policy areas, who do you think SHOULD have the most power and responsibility with respect to Wales? (weighted sample of 959 adults in Wales - 14-15 October 2023)

- Transport

- Housing

- Education

- Cultural issues

- Policing

- Environment

- Welfare

- NHS

- Gender reform

- The economy

- Immigration

- Foreign policy

Graph from polling carried out by Redfield and Wilton for Wales Online, October 2023.

Often, citizens’ primary concern is that services are delivered efficiently, effectively, and meet their needs. Where people have firm views about the division of policy responsibilities, this often depends on their perception of who is best able to deliver a high-quality service. This was a view presented to us repeatedly by citizens in the online surveys, the Community Engagement Fund reports and the citizens’ panels – the quality of public service delivery was the yardstick by which they measured the effectiveness of government, and for many it was a deciding factor for which constitutional framework they saw as best for Wales.

Protecting devolution

Welsh devolution is based on the outcome of 2 referendums and continues to enjoy popular support. It should not be eroded without the consent of citizens.

To recap, the key features of the current settlement are:

- Law-making powers on most domestic matters are devolved to the Senedd but the UK Parliament can pass laws affecting devolved matters without the Senedd’s agreement.

- Relations between the UK government and the devolved governments rely on convention. The initiative in these relations rests with UK government. The system was reformed, by agreement, in 2022 but still relies on the commitment of individual ministers.

- The powers devolved to Wales are broadly the same as Scotland, with the exception of justice and policing, some tax-varying powers, some social security benefits and some aspects of rail services.

The fundamental flaw in the current system of devolution is its vulnerability to unilateral change by a majority in the Westminster Parliament. This vulnerability is intrinsic to the devolution model which rests on powers conferred by the Westminster Parliament, which it can be taken away by the Westminster Parliament at any time.

Constraining the right of the UK Parliament to legislate as it sees fit could only be achieved by abandoning the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, which is widely seen as a cornerstone of the UK constitution (The contested boundaries of devolved legislative competence, 2023). It is difficult to envisage this occurring in the short to medium term. However, there are a range of measures that could, and should, be put in place to ensure that devolution is a stable and viable governance structure for Wales.

The inter-governmental process

The UK’s inter-governmental process is built on 2 foundations:

- Principle: the Sewel convention, which constrains Parliament in legislating on devolved matters. The Wales Act 2017 specifies that ‘it is recognised that the Parliament of the United Kingdom will not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters without the consent of the Assembly.’ The same provision for Scotland is included in the Scotland Act 2016.

- Practice: the inter-governmental arrangements established in 1999 and restructured in 2022, following a joint review by the 4 governments.

The most important elements of any inter-governmental process are:

- predictability

- a dispute resolution mechanism

- parity of esteem for each government’s electoral mandate

- procedures which all parties feel to be fair.

An effective process is essential to manage the interaction of responsibilities between the nations of the UK. Such interaction is unavoidable in any devolution settlement, and shared borders mean that it would persist under other constitutional models. Improving the relationship in a spirit of co-operation and parity of esteem, is essential, whatever option is pursued.

Shared governance is often undervalued as a feature of devolution. Whether a matter should be devolved or reserved is often seen as a binary question which overlooks the need for shared governance in relation to both devolved and reserved matters. The creation of a new internal market within the UK after Brexit has enhanced the scope for shared governance and makes good working relationships between governments considerably more important than it was in 1999. Further devolution of matters such as taxation have also increased the importance of shared governance.

Shared governance does not mean pitting the policy preferences of one government against the other. It means recognising each other’s interests and enabling tensions to be addressed through an agreed process. The findings of the transport sub-group (we discuss the sub-groups to the commission in chapter 5) on Wales’ rail infrastructure make a compelling case for greater use of shared governance on cross-border infrastructure.

The new structure of inter-ministerial groups creates a potentially coherent framework for shared governance, provided that the agendas and work plans cover the most important issues requiring co-operation between governments. It is essential that this structure develops to provide the continuity and stability that builds trust and shared understanding, so that it can sustain changes in personnel and become sufficiently robust to manage crises or disagreements when they arise.

Above all, effective inter-governmental relations are a priority for citizens. The changes we recommend below should be enacted by any government concerned about the stable and effective governance of the UK.

Lessons from federal systems

Differences between governments within a state are inevitable whatever their political affiliation, as seen in federal systems around the world.

Federal states such as Australia and Canada have well-established structures for relations between tiers of government. Typically, these are respected by all parties as necessary to the effective operation of the state, and are underpinned by a culture of co-operation and collaboration, or ‘federal spirit’, which includes:

- acceptance of the place and legitimacy of the sub-state institutions in the governance of the state as a whole

- a commitment for governing institutions at all levels to work together for the greater good

- respect for the underpinning machinery which facilitates such collaboration.

Features of internal relations in federal states

- Certainty: standing, formally established, structures linked to the constitution.

- Predictability: timetables are agreed in advance linked to the decision-making cycle

- Conflict management: conflict between levels of government is expected and provided for.

The state of inter-governmental relations

In 2022, the 4 governments of the UK agreed new inter-governmental arrangements, following the Dunlop Review established by Prime Minister Theresa May (Review of UK Government Union Capacity, 2019). The new structures have some of the features of a federal model, except that in the UK, the arrangements are discretionary, and there is no mechanism for challenging the decisions of the Treasury. More fundamentally, the collaborative ‘federal spirit’ is not a strong feature of inter-governmental relations in the UK.

The Sewel convention

The value of the Sewel convention (footnote 1) in protecting the powers of the devolved institutions is in doubt, because the UK government and Parliament have overridden it on numerous occasions since 2016, as discussed above. Many of these related to legislation directly or indirectly connected to Brexit, such as the EU Withdrawal Act and the Internal Market Act 2020. The UK government took the view that it is consistent with the Sewel convention for Westminster to legislate without consent in some circumstances, and that the legislation to implement Brexit was exceptional.

We accept that under the pressure to implement a working Withdrawal Agreement or face a no-deal Brexit, the UK government and Parliament felt it had to legislate without consent. However, this does not justify the unilateral process followed, including cutting the devolved governments out of the successor to EU structural funds, and making trade agreements detrimental to devolved interests. Nor does it justify failing to honour the commitments made to the devolved governments to engage them in the negotiations on exiting the EU.

The constructive joint work by the 4 governments on common frameworks (the common frameworks were a series of agreements for managing the powers previously exercised by the European Commission, and now exercised within the UK as a mix of devolved and reserved powers) is a notable exception to the decline in relations after Brexit. The House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee has suggested that the frameworks are at risk of becoming a missed opportunity, partly because the Internal Market Act 2020 and the Subsidy Control Act 2022 have ‘challenged the consensus approach taken in the common frameworks’ (Common frameworks: an unfulfilled opportunity?, 2022).

The evidence reaffirms the concerns we set out in chapter 7 of our interim report. We do not believe that the Sewel convention can be restored to its previous standing without reinforcement.

Procedural and legislative remedies

In the early stages of our work, it seemed that this problem was insoluble because the supremacy of the Westminster Parliament is seen as fundamental to the unwritten constitution of the UK. As we delved deeper, we discovered that there may be ways of constraining a Westminster Government with a majority in the House of Commons without calling into question the fundamentals of the British constitution.

Of course, any such constraints could be overturned by a subsequent government with a majority, in the same way as the Fixed-Term Parliament Act 2011 was repealed by the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022. However, changing constraints set in statute raises the political bar significantly, making it more difficult to unilaterally undermine the devolution settlement. We recommend the following provisions to achieve this:

Legislative provisions to protect devolution

- Putting into statute and making justiciable some key principles of inter-governmental relations and structures

- Putting into statute that the consent of the devolved institutions is required as a matter of law for any of the following:

- Any change of the scope of devolved legislative or executive powers

- Any other change to the devolution settlement

- Any exercise of legislative power by the UK Parliament within devolved competence, other than changes strictly required to fulfil the UK’s international obligations, maintain its defence or national security, or its macroeconomic policy

- Any exercise of executive power by UK government ministers within devolved competence

- Structuring the legislation enacting this in such a way that it could not readily be repealed or amended by a simple majority of the House of Commons without, at a minimum, significant reputational damage.

We suggest that these protections should apply to all 3 devolution settlements, if the legislatures and executives for Scotland and Northern Ireland support them. For Wales, we believe that these remedies are essential.

Inter-governmental mechanisms

In writing to Lord Dunlop in March 2021, the then Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Michael Gove, set out the UK government’s intentions (Letter from Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, 2021). He said that the objective was to create ‘a system of governance that will help build long term trust between governments’ and ‘support effective and regular consultation and, when appropriate, joint decision-making in areas of shared interest’.

Review of Inter-governmental Relations, January 2022

- A joint review by the 4 governments of the UK, with the report agreed by the heads of the 4 governments.

- The report proposed creating a new 3 tier structure:

- Tier 1 of portfolio Inter-Ministerial Groups

- Tier 2 of cross-cutting Ministerial Groups

- a top tier of Heads of Government.

- The report was based on a commitment to collaboration, trust and transparency.

- There would be an independent secretariat, recruited from the 4 governments, and a new independent arbitration mechanism binding on all departments except HM Treasury.

(Review of Inter-governmental Relations, 2022)

The evidence on progress towards this objective is mixed. The new arrangements announced by the 4 heads of government in 2022 make significant improvements, including the new structure of inter-ministerial groups dealing with 16 Whitehall portfolios.

These changes have the makings of a more effective structure, and the independent arbitration mechanism should enhance confidence and trust. However, excluding the decisions of HM Treasury from this mechanism is hard to justify, given the impact that Treasury decisions have on devolved government.

The Welsh Government’s report published in July 2023 identified a number of areas where practice in implementing the reforms has fallen short of the principles set out in the joint review. The key problems have been:

- limited involvement from the Prime Minister

- delay in convening some of the inter-ministerial groups

- questionable commitment from some UK ministers to the groups as forums for genuine engagement, which was not helped by the rapid turnover of UK ministers

- poor communication

- lack of preparedness for meetings

The evidence suggests that the potential of the new structures has not yet been fully tested. Genuine inter-governmental collaboration requires considerable energy and commitment across all parts of government and throughout the lifetime of an administration. This has been lacking in recent years.

A lack of respect for the devolved administrations, as elected legislatures and as executives accountable to their own electorate, undermines inter-governmental relations in the UK. While UK Parliamentary sovereignty is a cornerstone of the UK’s constitution, there is no legal basis for an ‘executive sovereignty’ that would justify seeing devolved governments as subordinate to UK government departments.

The culture, and working assumptions, of Whitehall does not hold the Welsh Government in parity of esteem. This is particularly the case with HM Treasury which seems to view the devolved governments as subject to its scrutiny in the same way as Whitehall departments.

Inter-governmental relations: tax and finance

In our interim report we said that the budget restrictions applied by HM Treasury undermine the Welsh Government’s ability to manage its budget and plan for the long term. Given the Welsh Government’s accountability to the Senedd’s Public Accounts Committee, and thus to its electorate, there is no justification for these restrictions.

The Welsh Government is seeking the following financial flexibilities to improve value for money. We believe the Treasury should accept these or explain its reasoning for withholding its agreement.

Borrowing and draw-down limits

The improvements made to the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework in relation to reserve and borrowing limits should be applied to Wales automatically without the need for a review of the Welsh Government’s Fiscal Framework. Applying the same arrangements for Wales would mean:

- Indexing their borrowing and overall reserve limits to inflation.

- The abolition of their reserve draw-down limits.

There is also a case for increasing capital borrowing limits.

Flexibility to manage in-year changes

Late changes to budgets present several challenges, including: difficulty in using large, unexpected allocations before the end of the financial year in ways which maximise value for money; and in managing large, unexpected cuts. Changes like those to the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework would help with this problem but might not be sufficient to deal with big additions or reductions late in the year. A principle should be established that funding changes confirmed after an autumn fiscal event can be managed across financial years, in addition to any carry forward permitted under reserve arrangements, to ensure effective budget management at the end of the financial year.

Large in-year announcements

The UK government should consider a solution similar to the Covid Guarantee when making decisions that potentially involve the allocation of substantial sums of money in-year. This would mean providing additional funding to devolved governments in good time, even when offsetting budget changes might affect overall funding levels later in the year. Any required changes could be reconciled later. This would give devolved governments some degree of certainty about the funding available ahead of the overall UK government departmental positions being finalised at UK Supplementary Estimates near the end of the financial year.

While the steps outlined above would represent a significant improvement over the status quo, we believe that in principle the Welsh Government should be free to manage its financial resources, with accountability to the Senedd, except where restrictions are necessary for the operation of UK macroeconomic policy, and that this principle should form the basis for future agreement between the Welsh and UK governments.

Devolved taxes

This raises the wider question of the UK government’s approach to proposals from the Welsh Government for new Welsh taxes. At present the Treasury requires a detailed policy justification for all proposals for new taxes. This can cause long delays and is incompatible with the Welsh Government’s accountability to the Senedd. The Welsh Government’s proposed Vacant Land Tax was considered to be a suitable start for the programme of developing new taxes. As HM Treasury has not completed its scrutiny after 4 years, it seems reasonable to conclude that this is intended to act as a block on innovation.

More widely, the scope for the Welsh Government to modify income tax is more limited than that of the Scottish Government. There is no case in principle for this different treatment. When the Welsh Government seeks further powers or greater flexibilities, in line with the other devolved governments, there should be a presumption of agreement unless there is a strategic case for continued reservation to the centre, in line with the recommendations we make later in the report for the exercise of powers.

The financial and tax flexibilities we propose can be made within the existing framework of the Barnett formula. Longer term, there is widespread recognition that the formula is an inadequate mechanism for determining the expenditure needs of the devolved nations. Devolution has evolved beyond recognition since it was introduced over 40 years ago, and there have been substantial changes over that time in the governance of the regions of England.

We believe that there is a growing case for a review of the funding of the devolved governments, jointly led by the UK and devolved governments. This review should consider from first principles how to allocate resources across the different parts of the UK, based on a shared assessment of relative needs and with a strong element of independent oversight.

Inter-governmental relations: data

The work of the commission sub-group on justice and policing (chapter 5) shows that the lack of Wales-specific data is a significant barrier to accountability and performance improvement. We have not taken evidence on data sharing in other areas but underline that Wales-specific data on reserved matters is essential to support better policy making. There should be a presumption in favour of compiling, sharing and publicising service data as a matter of routine.

Inter-governmental relations and the boundaries of the settlement

The failure of inter-governmental relations has led to poor policy outcomes at the boundaries of the devolution settlement. This is particularly the case for justice, and in transport. We explore the challenges that the current boundaries of devolution present for good governance and effective delivery in Chapter 5.

Policy innovation

One of the early arguments for devolution was to enable the devolved governments to try out new ideas, as happened with charging for plastic bags in Wales which was later adopted in the rest of the UK. Citizens, when polled, seem to prize policy uniformity across the UK, but support for policy uniformity drops when asked about policies where there has been significant divergence between nations such as prescription charges (The Ambivalent Union: Findings from the State of the Union Survey, 2023). It is also plausible that citizens in devolved nations believe there should be UK-wide uniformity with the policies in their nation, feeling that other parts of the UK should benefit from successful policies trialled ‘at home’.

All 4 governments have supported this policy laboratory approach in principle. In practice the political culture has been more suspicious, taking a ‘not invented here’ approach rather than embracing of diversity.

The British-Irish Council has been a more supportive context for shared learning, perhaps because it is more detached from internal UK politics.

Recent examples of Welsh devolution as a policy laboratory

Tax

As a new small body of 80 staff, responsible for 2 devolved taxes, the Welsh Revenue Authority has been able to innovate with a digital and partnership led business model. The UK government’s HM Revenue and Customs has taken a positive interest in the Authority’s approach and invited the Chief Executive to share learning with its staff.

Basic income pilot for care leavers

The Welsh Government is testing the impact of a minimum income on the prospects of young people leaving care, who are vulnerable and at risk of being drawn into offending and self-harming behaviour. UK government ministers have attacked the pilot in public and shown no interest in learning from it.

Asylum seekers

The commission’s welfare sub-group (chapter 5) explored with the Welsh Government the scope for an area-based pilot to test the impact on public services and tax revenues of reducing the barriers to asylum seekers seeking employment. They felt that such a pilot would be unlikely to gain UK government support, partly for policy reasons and partly because primary legislation would be required.

We recognise that these examples vary in their complexity, and that legislative competence can be a constraint. In a spirit of collaboration to facilitate new approaches, the UK government could confer competence on the relevant devolved legislature on a temporary basis to enable a policy pilot to be run.

This could be done through the Order in Council procedure provided for in the Government of Wales Act following the 2013 precedent when an order was made giving the Scottish Parliament temporary competence to legislate for an independence referendum. A pilot allowing asylum seekers greater access to work could be a possible use of such a power, with the Senedd given power for the lifetime of a Parliament to set up a scheme and see how it could work. The next UK Parliament could legislate if there was a desire to expand the pilot across the UK.

Conclusions

The mechanisms for managing devolution need to be strengthened to protect devolution in respect of the Sewel convention, inter-governmental relations and devolved financial management.

The effective conduct of relations between the 4 governments of the UK is too important to be left to the discretion of individual ministers. The only basis for successful relations is parity of esteem. Insofar as the UK government views the devolved governments as stakeholders to be managed, inter-governmental relations will be characterised by poor relations and poor outcomes. A spirit of genuine co-operation is needed, as exists in federal states. Those with long experience of the system can recall very few, if any, examples of where the UK government has announced that UK government policy has changed due to representations made following a formal meeting with the devolved governments.

A mature relationship would recognise that all governments have something to learn from each other. At times the UK government seems to see good relations as an optional extra; they are not. They are fundamental to the functioning of the countries of the UK jointly or separately.

Recommendations

To strengthen the mechanisms that protect devolution and to enable more effective management of the Welsh Government budget, we make the following recommendations. The legislative provisions required for recommendations 4 and 5 are set out above.

4. Inter-governmental relations

The Welsh Government should propose to the governments of the UK, Scotland and Northern Ireland that the Westminster Parliament should legislate for inter-governmental mechanisms so as to secure a duty of co-operation and parity of esteem between the governments of the UK.

5. Sewel convention

The Welsh Government should press the UK government to present to the Westminster Parliament legislation to specify that the consent of the devolved institutions is required for any change to the devolved powers, except when required for reasons to be agreed between them, such as: international obligations, defence, national security or macroeconomic policy.

6. Financial management

The UK government should remove constraints on Welsh Government budget management, except where there are macro-economic implications.

Footnotes

- The Sewel convention is strictly speaking one of interparliamentary relations, as it concerns legislation rather than executive functions. However, we are considering it in the context of a UK government party having a majority in the UK Parliament and therefore being able to direct the actions of the UK Parliament when legislating. (Back to text)