Future Trends Report Wales 2021: Narrative summary

The report has been designed to support the public sector in Wales in making better decisions for the long term.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Ministerial foreword

Countries across the world are dealing with complex and intergenerational challenges: a changing climate, increasing inequality, loss of biodiversity, the growing digitalisation of society, and the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. All of these threaten to leave people and places behind, and an unhealthy planet for future generations. The well-being of future generations approach we have here in Wales puts us in a stronger position to weather these changes, and seize the many opportunities to improve the quality of people’s lives across Wales in a sustainable way. It is an approach that is permeating our public services and is being recognised by business, the third sector, communities and citizens as the primary way to progress.

A key part of this approach is how we grapple with the future in significantly uncertain times. Public policy and decision making continues to be tested by the COVID-19 pandemic, and will be tested again as changes that may start on the other side of the planet find their influence across all of Wales. Our ability to shape the future of Wales, rests on our ability to shape our response to these big trends.

The Future Trends Report is therefore an important institutional mechanism in Wales, established under the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, to help policy makers understand Wales’ future and respond accordingly. Linked to the long-term way of working, 1 of the 5 ways of working that make up the sustainable development principle, the report complements evidence, analysis and resources across a range of policy areas to improve our ability to understand what may happen in the future.

The purpose of the report is to draw together, in one accessible place, a range of information to assist Welsh citizens and policy makers in understanding the big trends and drivers that are likely to shape Wales’ future. It has a specific role under the legislation to inform the work of Public Services Boards in their assessment of local well-being. The report also aims to support our national dialogue on how we can best prepare for the future. It should be seen as a resource document, a place where people can go to get information on key trends that prompts them to consider the challenges and opportunities these trends may bring.

The report features four megatrends which are most likely to pose risks or opportunities for Wales. These are, people and population, planetary health and limits, inequalities, and technology. Recognising the distinctive role that public bodies play in achieving the well-being goals the report, this time around, provides additional insight on the trends covering public finances and public sector demand and digital.

It does not provide the answers to some of these challenges, but by presenting them in an integrated resource it can help us understand and explore the links between them. Thinking about the long-term, coupled with the other ways of working: prevention, collaboration, involvement, and integration, when applied will help policy-makers navigate the compromises that inevitably feature in decision making.

Since the last report in 2017, we have seen significant events such as the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union and the COVID-19 pandemic which have brought major disruption to Wales. The pandemic has deepened inequalities and we have seen its disproportionate impact on some of the most vulnerable people in our society. I am passionate about the need to prepare our citizens and communities for the trends that are shaping how we live our lives, and the quality and resilience of our environment on which we depend. While this report acknowledges the pandemic as a key disruptor, its impact on long and medium-term future trends remains uncertain. In 2022, we will turn our focus to the potential long-term impact of the pandemic on the well-being of Wales and will provide an update in 2023. We will also continue to develop additional resources and opportunities to put long-term thinking into practice.

Futures, foresight and long-term thinking can easily appear to be far away from the immediate needs and strengths of people and communities. But we know that communities are engaged in shaping their communities. Earlier this year the Wales Council for Voluntary Action published their Better Futures Wales: Community Foresight project illustrates how futures methods can engage communities to imagine their own futures and create change. The Future Generations Commissioner for Wales is a vital part of this ecosystem, established with the general duty to promote the sustainable development principle and in particular encourage public bodies to take greater account of the long-term impact of the things that they do. I am also grateful to the Future Trends Report Steering Group and the Well-being of Future Generations National Stakeholder Forum for their contribution to this report.

Through the Well-being of Future Generations Act and its seven well-being goals, we have a framework for Wales’ future. A Wales that is economically, socially and environmentally just and a Wales we would want our children and grandchildren to inherit from us. Each one of us has a role to play. The Future Trends Report Wales 2021 provides an updated and robust starting point for decision-makers to explore the implications of these trends, so that we can better understand Wales’ future, driven by our solidarity to future generations.

Jane Hutt

Minister for Social Justice

Introduction

Looking to the future

Wales’ 7 well-being goals describe a sustainable future for Wales for people, for planet, for now, and for the future. Making progress towards these goals will require action from across all sectors, including government, public bodies, businesses, the third sector, and individuals.

The path towards these goals will not be straightforward and there are likely to be drivers and trends, some outside of the control of government that may accelerate or slow down progress. To be better equipped to understand these potential hurdles or opportunities, our well-being of future generations framework in Wales provides a mechanism to bring together the likely economic, social, environmental, and cultural trends into a single place. This is the through a Future Trends Report for Wales.

The first Future Trends Report was published in 2017 and looked at evidence of trends across a range of different policy themes. The 2021 report features and those big drivers of change where the trends are having an impact across all sectors, and have the potential for wider effects across the economy, society, environment, and culture. It focuses on the intergenerational challenges that Wales will need to respond to, and the areas it can shape for a more sustainable future.

While thinking about the future is a key part of strategy and policy making, the report does not cover the potential implications of trends or make suggestions for policy responses. It is not a statement of government policy. It is a resource to facilitate better-informed discussions by government, public bodies, the third sector, businesses, and communities. The report is specifically designed to be used by public bodies, Public Services Boards, and town and community councils, which the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (WFG Act) enables to think about the long-term. Bringing together trends into a single report is only one of the ways in which Welsh Government will support the futures ecosystem in Wales. The 2021 report will be part of a continuously evolving and improving future trends resource. The programme of work over the next 5 years will include an update to the report in 2023 to take account of the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the development of a methodology to test the sensitivity of the well-being goals to the key drivers and trends affecting Wales.

The Future Trends Report Wales 2021 is made up of the following resources:

- A narrative summary (this document), which provides a written overview of the key drivers and trends affecting Wales.

- An evidence pack, which provides the evidence base of the key drivers and trends affecting Wales through a series of 115 slides.

- An infographic, which provides an at-a-glance overview of the report.

Why do we produce a Future Trends Report?

The Future Trends Report Wales 2021 is a key part of the well-being of future generations framework in Wales. This framework is shaped primarily by the WFG Act, which puts in place a comprehensive sustainable development framework to improve the social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales for current and future generations. There are 7 connected well-being goals for Wales:

A prosperous Wales

An innovative, productive and low carbon society which recognises the limits of the global environment and therefore uses resources efficiently and proportionately (including acting on climate change); and which develops a skilled and well-educated population in an economy which generates wealth and provides employment opportunities, allowing people to take advantage of the wealth generated through securing decent work.

A resilient Wales

A nation which maintains and enhances a biodiverse natural environment with healthy functioning ecosystems that support social, economic and ecological resilience and the capacity to adapt to change (for example climate change).

A healthier Wales

A society in which people’s physical and mental well-being is maximised and in which choices and behaviours that benefit future health are understood.

A more equal Wales

A society that enables people to fulfil their potential no matter what their background or circumstances (including their socio economic background and circumstances).

A Wales of more cohesive communities

Attractive, viable, safe and well-connected communities.

A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language

A society that promotes and protects culture, heritage and the Welsh language, and which encourages people to participate in the arts, and sports and recreation.

A globally responsible Wales

A nation which, when doing anything to Thriving Welsh Language improve the economic, social, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales, takes account of whether doing such a thing may make a positive contribution to global well-being.

The 7 well-being goals aim to ensure that future generations have at least the same quality of life as we do now. The WFG Act enables better decision-making by ensuring that public bodies act in accordance with the sustainable development principle. Applying the principle means acting in a manner which seeks to ensure that the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This is about both inter-generational justice (between generations) and intra-generational justice (within generations). Public bodies need to make sure that when making their decisions they take into account the impact they could have on people living their lives in Wales in the future.

There are 5 ways of working that will enable organisations to work in this way. Following these ways of working will help us work better together, avoid repeating past mistakes and tackle some of the long-term challenges we are facing. These are:

- Take account of the long term

- Help to prevent problems occurring or getting worse

- Take an integrated approach

- Take a collaborative approach, and

- Consider and involve people of all ages and diversity.

Within the well-being of future generations framework we have statutory mechanisms to help understand Wales now and in the future. This includes the national well-being indicators and national milestones, as well as a duty on Welsh Ministers to prepare a Future Trends Report. This report has to be published every 5 years, within 12 months of a Senedd election. The report must contain predictions of likely future trends in the economic, social, environmental, and cultural well-being of Wales, any related analytical data and information that the Welsh Ministers consider appropriate.

In preparing the report, action taken by the United Nations (UN) in relation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment published under the Climate Change Act 2008 must be taken into account.

Public Services Boards in Wales are required to refer to the future trends report in their assessments of local well-being.

This report is one of many sources of evidence and tools that can help organisations facilitate future focussed conversations and analysis. A list of sources and tools is provided and kept up-to-date on our Future Trends Wales pages.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was agreed – the transformative plan of action based on 17 UN SDGs – to address urgent global challenges to 2030. It is through the action taken to achieve the 7 well-being goals by the public, private and third sector under the WFG Act that Wales will make its contribution to the achievement of the SDGs. In preparing this report, we have considered the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021 and the report of the UN Economist Network Shaping the Trends of Our Time (2020) which analysed global trends that are affecting the delivery of the SDGs. Closely aligning this report to our delivery of the UN SDGs, and taking action to achieve Wales’ 7 well-being goals ensures Wales is making its contribution to the achievement of the SDGs.

Understanding Wales’ future

Future generations framework

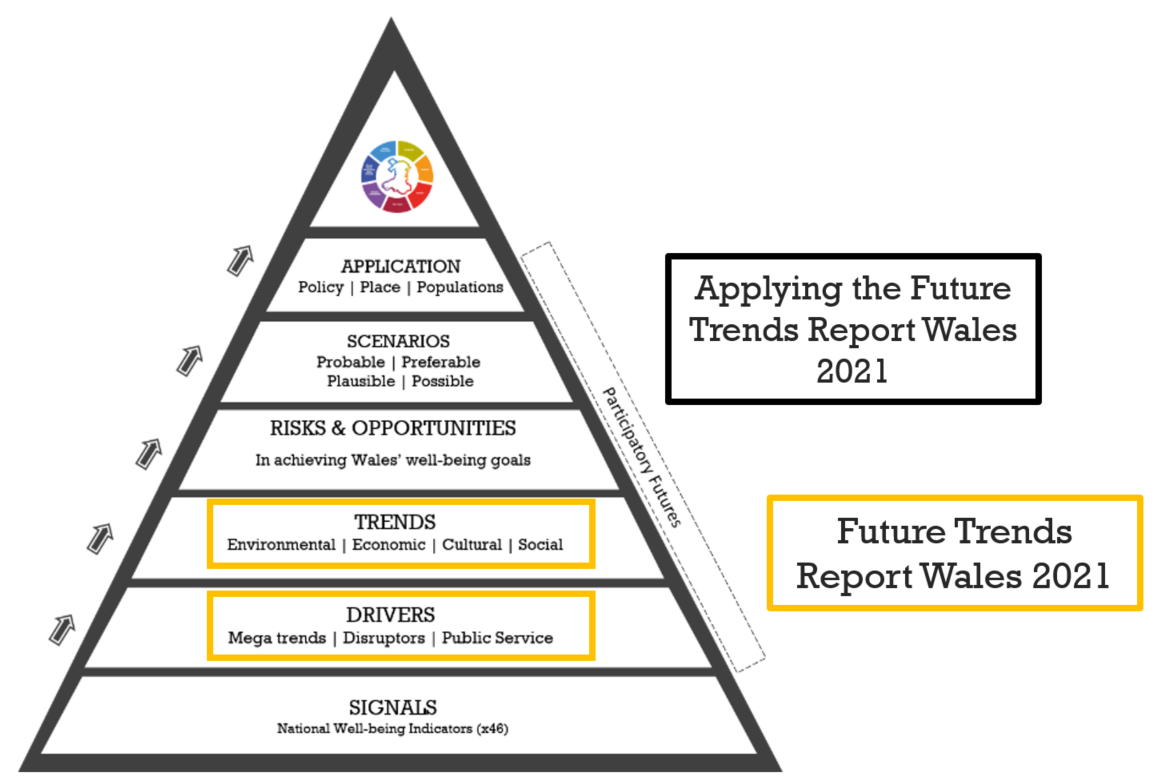

The well-being of future generations framework in Wales provides a means of understanding Wales’ future in a structured and systematic way. The publication of the Future Trends Report is one of the key features of this framework, but it sits alongside key activities and opportunities for how long-term thinking can be embedded into decision making within Wales. Figure 2 outlines the role of the report in the wider framework.

Signals

- tell us what is happening now. We have in place, through our 50 national well-being indicators, a means to track short term changes in Wales’ sustainability. These indicators cover the full range of aspects concerning Wales’ economy, society, environment and culture. They provide an annual update on a range of metrics, and contextual information that signal what change is happening and at what pace as we move towards the 7 well-being goals for Wales. We updated our suite of national well-being indicators in December 2021 to address gaps and better reflect the experience the pandemic. We report annually on their progress through a Well-being of Wales report published by the Chief Statistician for Wales.

Our national Well-being Indicators

- measure activity within Wales, but there may be signals outside of this framework that indicate future disruptions, risks and opportunities that may decelerate or accelerate progress towards the well-being goals.

Drivers

- are the most mature trends that are driving change across a wide range of well-being goals and influencing emerging trends. They have a greater influence across all the well-being domains of economy, society, environment and culture. They are often global in nature and intersect with each other to accelerate change – including those that may exacerbate existing problems such as inequality.

Trends

- are underlying patters of change that have a relatively clear direction of change.

Risks

- are the potential consequences of drivers and trends on achieving Wales’ well-being goals. Similarly, there may be drivers and trends that offer opportunities to accelerate progress towards the goals. Many of these risks and opportunities are interconnected.

Thinking about the long term can help the development of scenarios of alternative futures. The report can provide a platform and resource for policy teams and communities to develop possible, plausible, probable, and preferable futures.

Application of futures

- is about putting this evidence and tools on future into practice in different settings, whether this be looking at the future of a particular policy, a place or how certain trends will affect population groups differently, including people with protected characteristics.

Futures practice in Wales

While the practice of thinking about the future did not start with the passing of the WFG Act, the duties and emphasis within the legislation has seen greater activity and interest in the foresight and futures work within public policy in Wales. For example:

- The Future Generations Commissioner for Wales and their office have played a significant role in supporting and facilitating better consideration of the long-term within Wales. The Future Generations Report 2020 identifies some of the trends affecting Wales, and they have delivered and offer training and support on the application of the Three Horizons Toolkit.

- The Auditor General for Wales’ examinations recognised that if public bodies do not look to the future, they risk reducing well-being and increasing costs over the long term. The Auditor General’s work found many examples of where public bodies had thought about what they want to achieve over the long term, but highlighted the need for better planning for the future, informed by a rounded understanding of both current needs and future trends.

- Research by Cardiff University has explored emerging practice, identified the challenges that are emerging, and has outlined ways of enhancing the voice of future generations in public policy in Wales.

- A report by the School of International Futures looked at the features of effective systemic foresight in governments globally. The common set of features identified covered culture and behaviour, structures, people and processes. In their assessment, Wales’ innovative approach was recognised.

- Welsh Government have developed an internal foresight community to bring together officials from policy teams to share practice in applying futures work.

- Future Wales: the national plan 2040 identifies a number of challenges and opportunities to 2040 that have shaped the development of the national development framework.

- Public Health Wales and the Future Generations Commissioner’s Office developed a Three Horizons Toolkit to help public bodies avoid making decisions that do not stand the test of time. It is based on a model developed by Bill Sharpe and the International Futures Forum.

- The Better Futures Wales Project from the Wales Council for Voluntary Action encourages participants across 3 communities in Wales to dream about what a better future looks like for them and to develop an action plan for implementation.

- The Government Office for Science provided a brief guide to futures thinking and foresight, and published a Trend Deck providing and evidence base of long-term trends for UK policy makers.

- In September 2021, the UN Secretary-General published ‘Our Common Agenda’ which, for the first time, committed the UN to putting in place a range of institutional mechanisms to improve solidarity with future generations. It also recognised the importance of representing future generations as part of any country's approach to improving the lives of citizens and responsibility to the planet. This includes proposals for a declaration on future generations, a UN special envoy for future generations, and regular mechanisms to consider future trends. These changes are a strong endorsement of how Wales is working to embed the future in how Wales works.

- The State of Natural Resources Report (SoNaRR) contains the assessment of Wales’ sustainable management of natural resources, including Wales’ impact globally. SoNaRR 2020 builds on a number of Welsh, UK, and global assessments of the status and trends of natural resources. It looks at the risks those trends pose to our ecosystems and to the long-term social, cultural and economic well-being of Wales, in terms defined by the WFG Act.

Guide to the Future Trends Report Wales 2021

Trend selection

The trends featured in this report were identified following a literature review of the key trends that are shaping the global sustainable development agenda. A wide range of international and Wales/UK-level analysis and evidence sources were included in this review, a full list of which can be found in the ‘References and Resources’ section of the report’s Evidence Pack. These trends were appraised by Welsh Government departments and the Future Trends Report Technical Steering Group to establish the trends which are most significant to Wales’ well-being goals and should be featured in the 2021 report.

Structure

This report provides an overview of 4 big drivers of change:

- People and population

- Inequalities

- Planetary health and limits

- Technology

These trends are likely to affect Wales’ achievement of the seven well-being goals as they have potential implications across Wales’ society, economy, environment, and culture. Recognising the context in which public bodies and Public Service Boards, and town and community councils work, this report will also provide an overview of 2 public service drivers:

- Public finances

- Public sector demand and digital

The report summarises the key drivers and trends under these headings linked to the evidence pack. At the beginning of each section, an indicative analysis of the link between the drivers and Wales well-being goals is presented. We will be developing this analysis further through a sensitivity model to better understand the impact and opportunities these drivers present for each of the 7 well-being goals.

Ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Wales’ achievement of the well-being goals can be subject to disruption where a previously unknown event has a sudden and dramatic impact. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a disruptor affecting economic, social, environmental and cultural trends in Wales. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to renewed discussions and interest in futures foresight. The pandemic has had profound effects on economies and societies around the world, with some noticeable short-term disruptions to trends. It has had a significant impact on the global economy and has a disproportionate impact on developing countries, exacerbating poverty and highlighting global disparities in access to vaccines and recovery trajectories. Mirroring the global situation, the pandemic has amplified existing inequalities in Wales, particularly for the most vulnerable, but also more widely across society. Women, older people, young people, people from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups, disabled people, people with underlying health conditions, people living in substandard housing, and people working in informal, lower-income, and frontline service roles have all been disproportionately impacted.

It is likely that the ongoing pandemic will lead to the acceleration of some existing trends and potentially create new trends. However, how the evolving impact of pandemic will shape medium and long-term trends globally and for Wales is far more uncertain at this stage. This report acknowledges the impact of the pandemic but, given the uncertainty, it will not make any assumption on the certainty of the long-term impacts. We are planning an update to the evidence pack in early 2023 when further information and data becomes available.

People and population

Future population growth

While the global population is set to grow by 2 billion people by 2050, the rate of global population growth is set to decrease over time (United Nations, World Population Prospects 2019). The majority of global population growth will be outside of Europe and North America, with Africa displaying the highest population growth potential. It is possible that Africa will become the most populous continent by 2030, overtaking the populations of either China or India (UN, World Population Prospects 2019). Countries and regions around the world – including those in Wales – will experience population increases and demographic changes differently (Local authority population projections for Wales: 2018-based (revised), Welsh Government). Wales’ population currently stands at 3.17 million people and, based on current projections, this is expected to increase (Population projections by local authority and year, StatsWales), but is dependent on continued fertility and mortality rates as well as continued net in-migration, which may or may not occur.

Future population composition

Wales, like many economically developed countries, has an ageing population: people are living longer and having fewer children. Trends of decreasing mortality and fertility look set to continue, resulting in an increasing proportion of older people in the Welsh population. Compared to the UK as a whole, Wales is projected to continue having a higher share of older people in its population, and its working age population is set to gradually decrease in the coming decades (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government).

Healthy life expectancy

While estimates vary significantly, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy increases in Wales looked set to continue, although the rate of increase has slowed over the past decade (Life expectancy estimates, all ages, Office for National Statistics). However, this increase in life expectancy has not translated in to a higher ‘healthy life expectancy’ (the years someone spends in good health), which has decreased slightly in the past decade (Health state life expectancy, all ages, Office for National Statistics). This trend is driven, in part, by inequalities faced by those living in the most deprived areas in Wales, who are most likely to report ill health (Health state life expectancies by national depravation deciles, Wales: 2017 to 2019, Office for National Statistics). Ageing populations are also more associated with higher levels of chronic health conditions and ill health (Future of an Aging Population, Government Office for Science 2016; Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the UK, 2019-2040, London School of Economics and Political Science). However, older people tend to provide unpaid care and make valuable contributions to local communities.

Future household composition

The structure of households in Wales is changing. The number of households in Wales is projected to increase steadily over the next 20 years (Household projections by variant and year, StatsWales), however this is dependent on highly uncertain population projections. Trends of household composition point to increases in one-person households. Household sizes are becoming smaller in Wales, with the number of single-person households in projected to increase by over 10,000 in the period between 2020 and 2043 (Household projections by household type and year, StatsWales).

Migration

Migration is likely to continue to be a key driver of population change in Wales. Since 2019, there has been a shift in migration patterns which has led to an increase in net migration. Using the most recent population projections, international migration to Wales is assumed to be relatively constant up to 2030, with an expected net increase of around people 6,000 per year from mid-2025 onwards (National population projections, migration assumptions: 2018-based, Office for National Statistics). Non-EU net migration has been gradually increasing since 2013, and the year ending March 2020 saw some of the highest levels of non-EU migration to the UK since records began (Migration statistics quarterly report: August 2020, Office for National Statistics).

Welsh language

Over time, the number of welsh speakers in Wales is predicted to increase significantly. Projections based on 2011 census data, calculated in 2017 by the Welsh Government, estimated that there would be approximately 666,000 people aged 3 and over able to speak welsh by 2050 (Technical report: Projection and trajectory for the number of Welsh speakers aged three and over, 2011 to 2050, Welsh Government). This is equivalent to 21 per cent of the population and represents an increase of 100,000 Welsh speakers over the 40 year period. Taking into account policy assumptions in line with the Welsh Government’s target to reach 1 million Welsh speakers by 2050 (Cymraeg 2050: Welsh language strategy, Welsh Government), a separate ‘trajectory’ was produced indicating that this figure could be surpassed by 2030. Under this trajectory, the overall increase is assumed to be driven by younger age groups and maintained though future generations.

More recent data from the Annual Population Survey however, indicates that even the most ambitious estimates are currently being exceeded, with a reported 883,300 Welsh speakers aged 3+ in 2021 (Welsh language data from the Annual Population Survey: July 2020 to June 2021, Welsh Government). Despite a drop from 896,900 in 2019, the longer-term trend would suggest that the target of 1,000,000 Welsh speakers will be achieved far ahead of 2050, possibly even being surpassed within the next 10 years. It should be noted, however, that the National Census and Annual Population Survey use different sampling methods and are not therefore directly comparable. A more accurate picture of current Welsh language trends will be evident with the forthcoming publication of 2021 National Census data.

The ability to speak Welsh is most common among young people in Wales, with reported rates highest among those aged 19 and under. The proportion declines as respondents get older, slightly increasing for those aged 85 and over (Welsh language use in Wales - initial findings: July 2019 to March 2020, Welsh Government). While the proportion of those able to speak Welsh is highest in north Welsh local authorities, the rate of growth of speakers is highest in south and south east Welsh local authorities. Almost all Welsh speakers in Wales are also fluent English speakers.

For more detailed information on people and population trends, please view slides 8 to 31 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

Inequalities

Poverty

Globally, extreme poverty (people living on less than $1.90 a day) has declined over recent decades. As poorer countries become richer, inequality at the global scale is also decreasing (Shaping the trends of our time, United Nations). By international standards, income inequality in the UK is high, having risen sharply in the 1980s, but remaining broadly stable since the early 1990s (Income inequality in the UK, UK Parliament). Based on current trends, income inequality in the UK is likely to continue gradually increasing in the future as is inter-generational income inequality.

Wealth across the UK, like in many economically developed countries, is unequally divided (Shaping the trends of our time, United Nations). The richest households own a disproportionate and increasing proportion of the country’s total wealth, a trend that looks set to continue in the future (ibid.). With less wealth and fewer higher earners, Wales has lower levels of income and wealth inequality than many other parts of the UK (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government).

While many developing countries are making progress towards targets for reducing multidimensional poverty, several remain off track if observed trends continue (Shaping the trends of our time, United Nations).

Approximately one fifth of the Welsh population live in poverty (measured after housing costs - Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government). However, using relative income poverty as a measure, levels of poverty across Wales have gradually reduced since the mid-1990s (Percentage of all individuals, children, working-age adults and pensioners living in relative income poverty for the UK, UK countries and regions of England between 1994-95 to 1996-97 and 2017-18 to 2019-20, StatsWales). Poverty rates in Welsh households with a disabled person in the family are more than 10 per cent more likely to be living in income poverty, although the overall percentage has been gradually decreasing (People in relative income poverty by whether there is disability within the family, StatsWales). People from ethnic minorities (excluding White minorities) are also a more likely to live in relative income poverty in Wales, however the overall percentage has decreased significantly from 2014-15 levels (People in relative income poverty by ethnic group of the head of household, StatsWales). While non-working households continue to be at greatest risk of poverty, the share of poor people living in working households has increased over recent years as employment levels have increased (Working age adults in relative income poverty by economic status of household, StatsWales). Future trends in relation to poverty are uncertain and will depend particularly on UK government policy on welfare. In recent years, poverty rates for children in Wales have been broadly similar to the UK as a whole (Children in relative income poverty by economic status of household, StatsWales).

Educational attainment

Mirroring the UK as a whole, the qualification profile of the Welsh population has improved markedly in recent years (Examination results in schools in Wales, 2019/20, Welsh Government). However, an educational attainment gap at GCSE level remains, with Welsh students eligible for free school meals much less likely to achieve top grades than other students (GCSE entries and results pupils in Year 11 by FSM, StatsWales). The number of young people not in education, training, or employment in Wales has been falling over the past decade, but the rate of decrease has reduced in recent years.

Living standards

Living standards across different areas of Wales have become slightly more equal over time, although some progress has been reversed in recent years (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government). Since the 2008 financial crisis, the growth in both household incomes, and its main underlying driver productivity, in the UK have dropped well below the historic trend (Labour productivity time series, Office for National Statistics). Productivity, which is partly shaped by levels of education and skill, but also by population density and levels of urbanisation, is lower in Wales than in any other UK country or region except Northern Ireland. Flintshire, Wrexham, and the counties of south Wales have the highest rates of productivity in Wales, while Powys has the lowest productivity rate of all sub-regions in Britain (What are the regional differences in income and productivity? Office for National Statistics). The trend for median household incomes in Wales has followed the wider UK trend, although over recent years, median incomes in Wales have in broad terms been around 5 per cent lower than UK levels (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government).

Health inequalities

There are significant health inequalities affecting the lives of people in our society. Since the 1970s, multiple reports have highlighted the extent and effects of these in the UK and in Wales (Health state life expectancy, all ages, UK, Office for National Statistics). There are significant differences in ‘healthy’ life expectancy between the most and least deprived. Analysis (based on 2016-2018 data) shows that the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas was 9.0 years for men and 7.4 years for women (Past and projected period and cohort life tables, 2018-based, UK: 1981 to 2068, Office for National Statistics). However, the gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived was even greater, at 18.2 years for men and 19.1 years for women. Health inequalities can be deepened because of factors such as mental health problems, homelessness, and an inability to access healthcare.

Employment

Over the past 30 years, there has been an historic improvement in Wales’ rates of employment when compared with the UK as a whole, and, while rates have remained below the UK as a whole, Wales’ position in recent years has been better than in a number of other UK counties and regions (Labour market overview: October 2021, Welsh Government). Unemployment levels have been falling across Wales since 2013, although this is not occurring at an equal rate across the country – south east Wales has seen steep decreases in unemployment, whereas mid Wales has experienced very little change (ILO unemployment rates by Welsh local areas and year, StatsWales). Job creation in Wales has increased over the past decades but has occurred unevenly. Since 2001, Cardiff has had the largest proportionate increase of jobs in Wales during this time with a 45.5 per cent rise, which is consistent with its population growth over the last 2 decades. Meanwhile, Blaenau Gwent has seen the greatest proportional decrease in jobs at -19.1 per cent.

For more detailed information on inequalities trends, please view slides 32 to 49 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

Planetary health and limits

Climate change

Global temperatures have been steadily increasing over the past few decades – 9 of the 10 warmest years have been recorded since 2010 (Major update to key global temperature data set, Met Office). Climate-related disasters have increased dramatically, with less developed countries disproportionately affected. Climate change is widely expected to continue increasing the frequency, intensity, and impacts of extreme weather events in the coming years (State of the Global Climate, World Meteorological Organization). In Wales, there is a high probability that unprecedented weather events including coastal storms, flooding, heatwaves, and droughts will increase in the years ahead (Historic Environment and Climate Change in Wales, Cadw). Summers are projected to be warmer and drier, winters milder and wetter, and sea levels predicted to rise across the country by up to 24cm by 2050. In Wales, the impacts of climate change will not be felt equally across the country – economically and socially disadvantaged people will be disproportionately impacted (Climate change, justice and vulnerability, Joseph Rowntree Foundation). Existing inequalities are likely to be compounded, with people living in lower-income areas and more exposed locations having fewer available resources to mitigate and adapt to changes in the climate.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Global greenhouse gas emissions are growing at a rate of 1.5 per cent annually (Data supplement to the Global Carbon Budget 2021, ICOS). However, accelerated decarbonisation, advances in low-carbon technologies, and international decarbonisation pledges are expected to lead to a levelling off of global emissions (Shaping the trends of our time, United Nations). In Wales, domestic greenhouse gas emissions have fallen by almost a third since 1990 (Devolved administration emission inventories, National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory). This reduction is predominantly due to transformations in the power sector, particularly through the phasing out of coal-fired power generation. The rate of reduction in emissions in Wales has slowed in recent years (2021 Progress report to parliament, Climate Change Committee). Emissions from agriculture have fallen by 11 per cent since 1990, but have increased by 13 per cent in the last decade (ibid.). Stark emissions inequalities exist between the wealthiest and poorest people. This trend looks set to continue at both the global and national level. The richest 10 per cent of the UK population are responsible for a quarter of UK total emissions, producing over 4 times more emissions than the poorest 50 per cent (Carbon emissions and income inequality, Oxfam Library; Emissions gap report 2020, United Nations).

Sustainable consumption

Wales, like many economically developed countries, is using both renewable and non-renewable natural resources at an unsustainable rate. If everyone on Earth used natural resources at the same rate as Wales, 2.5 planets would be needed (Scientists’ warning on affluence, Nature Communications). This overconsumption and overproduction is driving the depletion of the heavily relied upon natural resources of developing countries, who tend to be more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Energy use

Since 2005, the introduction of energy efficiency measures in Wales has led to a reduction in energy use (Energy Generation in Wales 2019, Welsh Government). As a share of overall energy use in Wales, transport-related energy use has increased, whereas industry-related energy use has decreased. Agriculture and building-related energy use has remained broadly the same (Energy use in Wales 2018, Welsh Government). The Committee on Climate Change projects a likely doubling of electricity demand in Wales by 2050 due to new demands from the societal transition to renewable electricity sources (Independent Assessment of UK Climate Risk, Climate Change Committee).

Air pollution

Air pollution is one of the world’s largest health and environmental problems, contributing to 9 per cent of deaths globally. Although the global death rate from air pollution has fallen over recent decades, there are persistent social and environmental costs, including through degrading habitats and waterways. While some areas of Wales benefit from some of the best air quality in the UK, south Wales has some of the worst levels of air pollution. Public Health Wales estimates that up to 1,400 deaths each year can be attributed to air pollution (Air pollution and health in Wales, PHW). Air pollution is highest in Wales’ most deprived areas. While nitrogen dioxide emissions levels have been gradually declining over the past decade, in recent years particulate matter levels have been increasing following a period of decline to record low values in 2017 (Concentrations of nitrogen dioxide, Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs).

One of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution in Wales is transportation. Over the past decade, the distance driven by cars in Wales has increased by 13 per cent, while the emissions from these cars has fallen by 9 per cent (2021 Progress report to parliament, Climate Change Committee). Despite these efficiency improvements, overall surface transport emissions have remained mostly unchanged from 1990 levels. Based on current trajectories, car traffic in Wales is increasing. Travel by van and rail have seen significant increases in the last decade, whereas travel by bus has decreased. Cycling demand has more than doubled in the past decade, but still accounts for a very small share of overall travel. The popularity of electric vehicles has also risen sharply across the UK in recent years – a trend which is set to continue and is likely to reduce overall car emissions (Statistical Dataset - All Vehicles, GOV.UK).

Biodiversity and ecosystems

Biodiversity loss is accelerating both globally and in Wales at an unprecedented rate (Global Biodiversity Outlook 5, Convention on Biological Diversity). While populations of some species in Wales have improved (e.g. birds, bats, and freshwater species), serious declines have been reported in other species (e.g. butterflies, moths, invertebrate species, and many plant species - State of Natural Resources Report (SoNaRR): Assessment of the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources, Natural Resources Wales). 17 per cent of species found in Wales are in danger of becoming extinct in the country (The State of Nature 2019: A Summary for Wales, National Biodiversity Network). This biodiversity loss is having a direct impact on Wales’ ecosystems, which currently have low resilience (State of Natural Resources Report (SoNaRR): Assessment of the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources, Natural Resources Wales).

While the quality of water in Wales, whether in seas, rivers, streams or the ground, is generally improving, nitrogen-based pollution from agriculture is severely damaging biodiversity and ecosystems, leading to eutrophication and acidification of waterways and soils. Modest reductions in agricultural nitrogen emissions are projected by 2030 (Nitrogen Futures, Joint Nature Conservation Committee).

Crop yields

The impacts of climate change are projected to reduce global crop yields from 2030 onwards, with nearly half of projections beyond 2050 indicating yield decreases greater than 10 per cent (A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaption, Nature Climate Change). This impact is likely to be most acutely felt in developing countries and countries most at risk from the impacts of climate change (World development report 2010: Development and climate change, World Bank). Wales, like the UK as a whole, is currently reliant on food imports from other countries (UK's fruit and vegetable supply increasingly dependent on imports from climate vulnerable producing countries, Nat Food) , many of which are vulnerable to reductions in crop yields.

Food demand

To meet the demand for food in 2050, it is estimated that global agricultural production will need to increase by 50 per cent from 2012 levels (World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN). While projected increases in food production may reduce global levels of hunger and malnutrition, growth in agricultural emissions, food waste, and obesity are also to be expected. The global food system is responsible for between 21 and 37 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions (Climate change and land - Chapter 5: food security, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Based on current methods of food production, processing, storage, transport, and packaging, these emissions are expected to increase to between 30 and 40 per cent by 2050 alongside the potential additional ecological degradation they currently entail.

Food security

Increased threats to food security, driven in part by the impacts of climate change and unsustainable practices, is likely to result in increases in the prices of some foods, such as cereals (ibid.). Certain crops grown in environments with higher carbon dioxide levels have also been shown to produce less nutritious food, which risks increasing nutritional deficiencies in the decades ahead.

For more detailed information on Planetary Health and Limits trends, please view slides 50 to 73 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

Technology

Internet usage and access

Internet usage is increasing across Wales and the UK as a whole. The number of proportion of adults in Wales who do not use the internet has dropped to around 10 per cent (Internet Users, Office for National Statistics). However, the proportion of people aged 75 and over in the UK who do not use the internet is increasing. This age group also uses the internet ‘on the go’ far less than other adults – a trend which decreases with age (Exploring the UK's Digital Divide, Office for National Statistics).

Despite an overall increase in internet usage, a ‘digital divide’ remains between those with and without the skills and access to information and communications technologies (National survey for Wales: Results viewer, Welsh Government). This persisting divide can exacerbate social and economic inequalities for the digitally excluded (Providing basic digital skills to 100% of UK population could contribute over £14 billion annually to UK economy by 2025, The Centre for Economics and Business Research). The most digitally excluded people in the Welsh population are those aged 75 and above.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

While the use of artificial intelligence is increasingly part of everyday life in Wales, the future trajectory of AI presence and usage in Wales is uncertain and is highly dependent on how prepared or willing society is to further adopt AI technologies. Recent years have seen growing ethical concerns on the use and aims of AI adoption, and it can be expected that ethical considerations will feature more centrally in decision-making on AI use in the future (Cyber Security Breaches Survey, Ipsos Mori).

Digitalisation

Globally, businesses are increasingly adapting to digitalisation and adopting new technologies. The overarching trend is one of accelerating digitalisation of work processes. In the near future, the adoption of encryption and cyber security technologies is projected to increase by 29 per cent, while the adoption of cloud computing is estimated to rise by 17 per cent (The future of jobs report 2020, World Economic Forum). Evidence indicates that there is a trend in the UK towards increasing provision of remote working opportunities (Doing what it takes: Protecting firms and families from the impact of coronavirus, Resolution Foundation). However, this trend varies significantly depending on an individual’s industry and occupation – those in customer facing, skilled trade roles are less likely to work remotely, whereas public administration and managerial roles are most flexible in terms of remote working. Remote working trends will have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and these trends will be analysed as part of the 2023 update to the report. Alongside the growth of digitalisation, cybersecurity threats are posing an increasing danger to all societies. 82 per cent of UK businesses use online banking and 58 per cent hold personal information about customers electronically. 40 per cent of UK businesses have experienced data breaches or attacks within the last 12 months (Cyber Security Breaches Survey, Ipsos Mori). Cybersecurity is likely to become increasingly salient if current trends continue.

Job automation

The trend towards further automation of work is likely to continue with increasing use of technology in substituting labour as well as further embedding technology within existing workplaces and working practices with the aim of generating new and improved opportunities, products, and services (Wales 4.0 Delivering economic transformation for a better future of work, Welsh Government). It is estimated that around 6.5 per cent of jobs in Wales have a ‘high potential for automation’, a figure slightly above the UK average of 6.2 per cent (Shaping the future: A 21st century skills system for Wales, IPPR Scotland). Evidence suggests ‘low-skilled’ roles involving routine and repetitive tasks are considered at greatest risk of automation, while ‘high skilled’ roles involving varied and complex tasks are less likely to be automated (Which occupations are at the highest risk of being automated? Office for National Statistics). Younger people and women are more likely to be at risk of having their job automated in the future (The probability of automation in England: 2011 to 2017, Office for National Statistics).

Digital skills

Almost 1 in 5 people in Wales lack basic digital skills, the highest proportion of any UK region. Wales also has the fewer people reporting good digital skills than other UK regions (Essential digital skills report 2021, Lloyds Bank). Digital skills are increasingly sought after by employers for jobs at all skill levels; 77 per cent of ‘low skilled’ job roles in the UK are in occupations that require digital skills (No longer optional: Employer demand for digital skills, Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport). The demand for skills relating to computer and networking support is 5 per cent higher in Wales than the UK average (ibid.). Evidence suggests technology-related skills will account for the most valued skills by 2025 (The future of jobs report 2020, World Economic Forum). However, areas that cannot be replicated easily through the use of technology such as emotional intelligence, persuasion and negotiation, will retain their value and remain in demand for the foreseeable future.

For more detailed information on technology trends, please view slides 74 to 86 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

Public finances

The pandemic has had major economic effects over the last 2 years, but the longer term implications are generally uncertain. Therefore, this section focuses mainly on short to medium-term trends.

Overview

GDP is projected to grow following a drop during the pandemic, however projections for recovery vary (Monetary Policy Report: November 2021, Monetary Policy Committee). UK public sector net borrowing declined as a share of GDP throughout the last decade and is expected to continue to fall in future years (Public finances databank: October 2021, Office for Budget Responsibility). Devolved tax revenues are forecast to grow over the next 5 years (Overview of the March 2021 Economic and fiscal outlook, March 2021 devolved tax and spending forecasts: charts and tables, Office for Budget Responsibility). A declining working age population may impact upon future levels of tax revenue (Principal projection: Wales population in age groups, Office for National Statistics (Principal projection: UK population in age groups, Office for National Statistics). The longer term outlook for the Welsh Government’s finances will be considered in the Chief Economist’s Report accompanying the draft Budget.

Employment and qualification

Over the period since the mid-1990s, the historic gap in employment rates between Wales and the rest of the UK has narrowed, and over the recent past the labour market in Wales has performed as well or better than a number of other UK countries and regions (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government). At the same time, there is no sign that the average “quality” of jobs in Wales has declined, although there is clearly scope for improvement in this regard. Qualification levels in Wales have improved, though not as much as in some other parts of the UK (Examination results in schools in Wales 2019/20, Welsh Government).

Productivity

Over the long term, improvements in wages and living standards are dependent upon increases in productivity. As with other parts of the UK, productivity growth in Wales has been weak since around the time of the financial crisis (Labour productivity time series, Office for National Statistics). The UK as a whole compares poorly with other countries in terms of its level of labour productivity, and, in turn, Welsh performance is weaker than most other parts of the UK. The gap in productivity between Wales and the UK as whole widened over the years leading up to the financial crisis, but has been broadly unchanged since. However, average (median) pay in Wales has in broad terms kept pace with the UK since around the time of devolution (Chief Economist's Report 2020, Welsh Government).

Living standards

Living standards in Wales, as reflected in median incomes, are around 5 per cent below those in the UK as whole (ibid). This gap is much smaller than the gap in GDP per head, mainly reflecting large transfers under the UK’s fiscal system. Differences in living standards between different areas of Wales have narrowed over the period since the late 1990s, though this trend may have partially reversed since around 2013.

Incomes and income inequality

Changes in Welsh median incomes track the UK as whole quite closely over the medium term. As with the UK as a whole, the improvement in Welsh living standards has been sluggish in recent years, largely in response to the weak underpinning productivity growth (ibid).

Income inequality across the UK widened sharply during the 1980s, but has been broadly unchanged since (with some fluctuation). However, there was a modest increase in inequality across the UK over the period immediately before the pandemic, and some indications that one of the lasting effects of the pandemic will be to further increase inequality, as the disruption to education has impacted differentially (ibid). Children and young people from lower income backgrounds have been particularly affected and this may have lasting consequences.

While income inequality has been broadly unchanged over the medium to longer term, relative poverty in Wales has, if anything, declined, though this decline occurred in the period prior to 2010 (ibid). Future prospects for relative poverty depend to a large extent on UK government policy decision on taxes and benefits.

Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

The trend towards remote and home working has been accelerated by the pandemic and this is likely to have lasting implications for travel patterns and the location and nature of certain types of activity and employment (ibid).

Despite increases in funding by the UK government as a result the pandemic, the longer run fiscal position facing the Welsh Government is challenging, with particular risks resulting from a range of factors, including demographic change.

For more detailed information on public finances, please view slides 87 to 92 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

Public sector demand and digital

Supporting an ageing population

It is expected that Wales’ ageing population will increase the demand for public services in the medium to long term. As populations age, there is likely to be a greater proportion of people experiencing chronic health conditions and multi-morbidities, both of which increase cost and resource pressures on health and social care services. Current projections estimate that to meet demand, expenditure on health will grow from 7.3 per cent of GDP in 2014-15 to 8.3 per cent in 2064-65 and from 1.1 to 2.2 per cent of GDP on long term care up during the same period (Future of an Aging Population, Government Office for Science).

Projections show that within Wales and the UK as a whole, the old age dependency ratio, which gives an approximation of the number of people being supported by the working age population, will drop considerably over time until 2037 (Living longer and old-age dependency: what does the future hold? Office for National Statistics). This means that the number of those most likely to require publically funded services will increase relative to the number of economically active people that are able to provide tax revenue.

Public sector employment

Following a decade of decline, the number of people employed within the Welsh public sector has increased to its highest ever point, growing 13.3 per cent in recent years to 30.6 per cent of Wales’ total workforce (Employment in the public and private sectors by Welsh local authority and status, StatsWales). It is unclear whether the trend will continue as recent workforce increases may be attributable to the public sector’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, over the past decade, the public sector’s productivity has been on an increasing trend (Public service productivity: total, UK, 2018, Office for National Statistics).

Online public service use

The way in which people access public services is changing. The trend in increasing internet use has also led to growth in online use of public services, and a general increase in the obtaining of information, downloading, and submitting of official forms online (Internet skills and online public sector services: April 2019 to March 2020, Welsh Government). The latest evidence suggests that 77 per cent of respondents in Wales have used at least one public service website within the last 12 months, with those aged 35-54 most likely to access public service websites, and those aged 65 and over least likely (National survey for Wales: Results viewer, Welsh Government).

For more detailed information on public sector demand and digital trends, please view slides 93 to 101 of the Future Trends Report Wales 2021 Evidence Pack.

References and resources

People and population: reports

- Bevan Foundation. (2018). Demographic Trends in Wales. Merthyr Tydfil: Bevan Foundation.

- CPEC. (2019). Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the United Kingdom, 2019-2040. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Government Office for Science. (2016). Future of an Aging Population. London: Government Office for Science.

- ONS. (2019a). Past and projected period and cohort life tables, 2018-based, UK: 1981 to 2068. Online: Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2019c). National population projections, migration assumptions: 2018-based. Online: Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2020). Migration statistics quarterly report: August 2020. Online: Office for National Statistics

- ONS. (2021c). Health state life expectancies by national depravation deciles, Wales: 2017 to 2019. Online: Office for National Statistics.

- United Nations. (2019a). World Population Prospects 2019. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations. (2020). World Population Aging 2019. New York: United Nations.

- Welsh Government. (2017a). Technical report: Projection and trajectory for the number of Welsh speakers aged three and over, 2011 to 2050. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2017b). Cymraeg 2050: Welsh language strategy. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2020b). Local authority population projections for Wales: 2018-based (revised). Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2020d) Subnational household projections (local authority): 2018 to 2043. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2020e). Estimates of additional housing need in Wales (2019-based). Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2021f). Welsh language data from the Annual Population Survey: July 2020 to June 2021. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2021g). Welsh language use in Wales (initial findings): July 2019 to March 2020. Welsh Government.

People and population: datasets

- ONS. (2019b). National population projections table of contents. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021a). Life expectancy estimates, all ages, UK. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021b). Health state life expectancy, all ages, UK. Office for National Statistics.

- United Nations. (2019b). World Population Prospects 2019. Department of Economic and Social Affairs:

- Welsh Government. (2020a). Population projections by year and age. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2020c). General health and illness by WIMD deprivation quintile. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2020f). Average annual estimates of housing need (2019-based) by region, variant and year (5 year period). StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021a). Population projections by local authority and year. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021b). Household projections by household type and year. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021c). Household projections by variant and year. StatsWales.

Inequalities: reports

- House of Commons Library. (2021). Income inequality in the UK. UK Parliament.

- ONS. (2021b). What are the regional differences in income and productivity? Office for National Statistics.

- United Nations. (2020a). Shaping the trends of our time. United Nations.

- Welsh Government. (2020a). Examination results in schools in Wales, 2019/20. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2020b). GCSE entries and results pupils in Year 11 by FSM. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2020c). Chief Economist's Report 2020. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2021g). Labour market overview: October 2021. Welsh Government.

Inequalities: datasets

- ONS. (2020a). Regional gross disposable household income: local authorities by ITL1 region. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021a). Labour productivity time series. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021c). LFS: Employment rate: Wales: Aged 16-64: All: %: SA. Office for National Statistics.

- UK government. (2021). Explore education statistics. GOV.UK.

- United Nations. (2020c). Multidimensional poverty index. United Nations.

- United Nations. (2021). World Income Inequality Database. United Nations University.

- Welsh Government. (2020b). GCSE entries and results pupils in Year 11 by FSM. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021a). Percentage of all individuals, children, working-age adults and pensioners living in relative income poverty for the UK, UK countries and regions of England between 1994-95 to 1996-97 and 2017-18 to 2019-20. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021b). People in relative income poverty by whether there is disability within the family. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021c). People in relative income poverty by ethnic group of the head of household. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021d). Working age adults in relative income poverty by economic status of household. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021e). Children in relative income poverty by economic status of household. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021f). ILO unemployment rates by Welsh local areas and year. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021h). Workplace employment by Welsh local areas and year. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021i). Highest qualification levels of working age adults by UK country, region and qualification. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021j). Highest qualification levels of working age adults by UK country, region and qualification. StatsWales.

Planetary health and limits: reports

- Air Quality Expert Group. (2019). Non-Exhaust Emissions from Road Traffic. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs.

- Cadw. (2020a). Historic Environment and Climate Change in Wales.

- CGIAR. (2020). Big facts on climate change, agriculture and food security. Big Facts.

- Challinor, A. J., Watson, J., Lobell, D. B., Howden, S. M., Smith, D. R., & Chhetri, N. (2014). A meta-analysis of crop yeild under climate change and adaption. Nature Climate Change.

- Climate Change Committee. (2021a). Independent Assessment of UK Climate Risk. Climate Change Committee.

- Climate Change Committee. (2021b). 2021 Progress report to parliament. Climate Change Committee.

- Convention on Biological Diversity. (2020). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Montreal.

- DEFRA. (2021a). Concentrations of nitrogen dioxide. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs.

- FAO. (2012). World agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 revision.

- Hanlon, H. M., Bernie, D., Carigi, G., & Lowe, J. A. (2021). Future changes to high impact weather in the UK. Climate Change, 166(50).

- IPCC. (2019). Chapter 5: food security. In Climate change and land. 437-550.

- JNCC. (2020). Nitrogen Futures. Peterborough.

- Johnson, C. N. (2021). Past and future decline and extinction of species. The Royal Society.

- Lindley, S.; O'Neill, J.; Kandeh, J.; Laweson, N.; Christian, R.; O'Neill, M. (2011). Climate change, justice and vulnerability. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Met Office. (2020a). Major update to key global temperature data set. Met Office:

- National Biodiversity Network. (2019). The State of Nature 2019: A Summary for Wales. NBN.

- NRW. (2016). State of Natural Resources Report (SoNaRR): Assessment of the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources. Natural Resources Wales.

- NRW. (2020). SoNaRR 2020: Bridges to the future. Natural Resources Wales.

- Oxfam. (2015a). Carbon emissions and income inequality. Oxfam Library.

- PHW. (2020). Air pollution and health in Wales. PHW.

- Scheelbeck, P. F., Moss, C., Kastner, T., Alae-Carw, C., Jarmul, S., Green, R., Dangour, A. D. (2020). UK's fruit and vegetable supply increasingly dependent on imports from climate vulnerable producing countries. Nat Food, 705-712.

- United Nations. (2018a). Inclusive wealth report 2018. Nairobi: United Nations.

- United Nations. (2020a). Shaping the trends of our time. United Nations.

- United Nations. (2020b). Emissions gap report 2020. Nairobi: United Nations.

- Welsh Government. (2020a). Energy Generation in Wales 2019. Regen.

- Welsh Government. (2020b). Energy use in Wales 2018. Regen.

- Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Keyßer, L. T., & Steinberger, J. K. (2020). Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nature Communications, 1-10.

- WMO. (2021a). State of the Global Climate. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization.

- World Bank. (2010). World development report 2010: Development and climate change. Washington DC: World Bank.

- WWF. (2020). Living planet report 2020. Gland.

Planetary health and limits: datasets

- DEFRA. (2021b). UKEAP: National ammonia monitoring network. UK Air Information Resource.

- Department for Transport. (2021a). Statistical Dataset - All Vehicles. GOV.UK.

- Department for Transport. (2021b). Table Catalogue. Department for Transport.

- Global Carbon Budget. (2021). Data supplement to the Global Carbon Budget 2021. ICOS.

- Met Office. (2021a). Download and view UK Climate Projections data. Met Office.

- NAEI. (2021a). Devolved administration emission inventories. National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory.

- NAEI. (2021b). Devolved administration emissions by source. National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory.

- Our World in Data. (2020). Agricultural Production. Our World in Data.

Technology: reports

- Burning Glass Technologies. (2019). No longer optional: Employer demand for digital skills. London: Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport.

- CEBR. (2015). Providing basic digital skills to 100% of UK population could contribute over $14 billion annually to UK economy by 2025. The Centre for Economics and Business Research.

- DDCMS. (2021). Cyber Security Breaches Survey. London: Ipsos Mori.

- IBM. (2020). Artificial Intelligence (AI). IBM Cloud Education.

- IPPR Scotland. (2020). Shaping the future: A 21st century skills system for Wales. Edinburgh.

- Lloyds Bank. (2021). Essential digital skills report 2021.

- McKinsey. (2019). Artificial intelligence in the United Kingdom: Prospects and challenges. McKinsey Global Institute.

- ONS. (2019a). Exploring the UK's Digital Divide. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2019b). Which occupations are at the highest risk of being automated? Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2019c). The probability of automation in England: 2011 to 2017. Office for National Statistics.

- Resolution Foundation. (2020). Doing what it takes: Protecting firms and families from the impact of coronavirus. London.

- Welsh Government. (2019a). Wales 4.0 Delivering economic transformation for a better future of work.

- World Economic Forum. (2020). The future of jobs report 2020. Geneva.

Technology: datasets

- ONS. (2021a). Internet Users. Office for National Statistics.

- Welsh Government. (2021a). National survey for Wales: Results viewer.

Public finances: reports

- Bank of England. (2021). Monetary Policy Report: November 2021. Monetary Policy Committee.

- HM Treasury. (2021). Budget 2021: Protecting the jobs and livelihoods of the British people.

- OBR. (2021a). Economic and fiscal outlook: March 2021. Office for Budget Responsibility.

- OBR. (2021c). Overview of the March 2021 Economic and fiscal outlook. Office for Budget Responsibility.

- The Health Foundation. (2016). The path to sustainability.

- Welsh Government. (2020c). Chief Economist's Report 2020. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2021). Annual Budget Motion 2021-22.

Public finances: datasets

- OBR. (2021b). Public finances databank - October 2021. Office for Budget Responsibility.

- OBR. (2021d). March 2021 devolved tax and spending forecasts - charts and tables. Office for Budget Responsibility.

- ONS. (2019a). Principal projection - Wales population in age groups. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2019b). Principal projection - UK population in age groups. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021a). Labour productivity time series. Office for National Statistics.

Public sector demand and digital: reports

- GoS. (2016). Future of an Aging Population. London: Government Office for Science.

- Nuffield Trust. (2021). The remote care revolution during Covid-19. Quality Watch.

- ONS. (2019b). Living longer and old-age dependency - what does the future hold? London: Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021a). Public service productivity: total, UK, 2018. Office for National Statistics.

- Welsh Government. (2021). Employment in the public and private sectors by Welsh local authority and status. StatsWales.

- Welsh Government. (2021b). Internet skills and online public sector services (National Survey for Wales): April 2019 to March 2020.

Public sector demand and digital: datasets

- NHS. (2021). Appointments in General Practice - September 2021. NHS Digital.

- ONS. (2019a). Expectation of life, principal projection, Wales. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2020). Internet access - households and individuals. Office for National Statistics.

- ONS. (2021b). Public service productivity, quarterly. Office for National Statistics.

- Welsh Government. (2021c). National survey for Wales: Results viewer. Welsh Government.